Guest Post: The Mental Burden of Research Participation

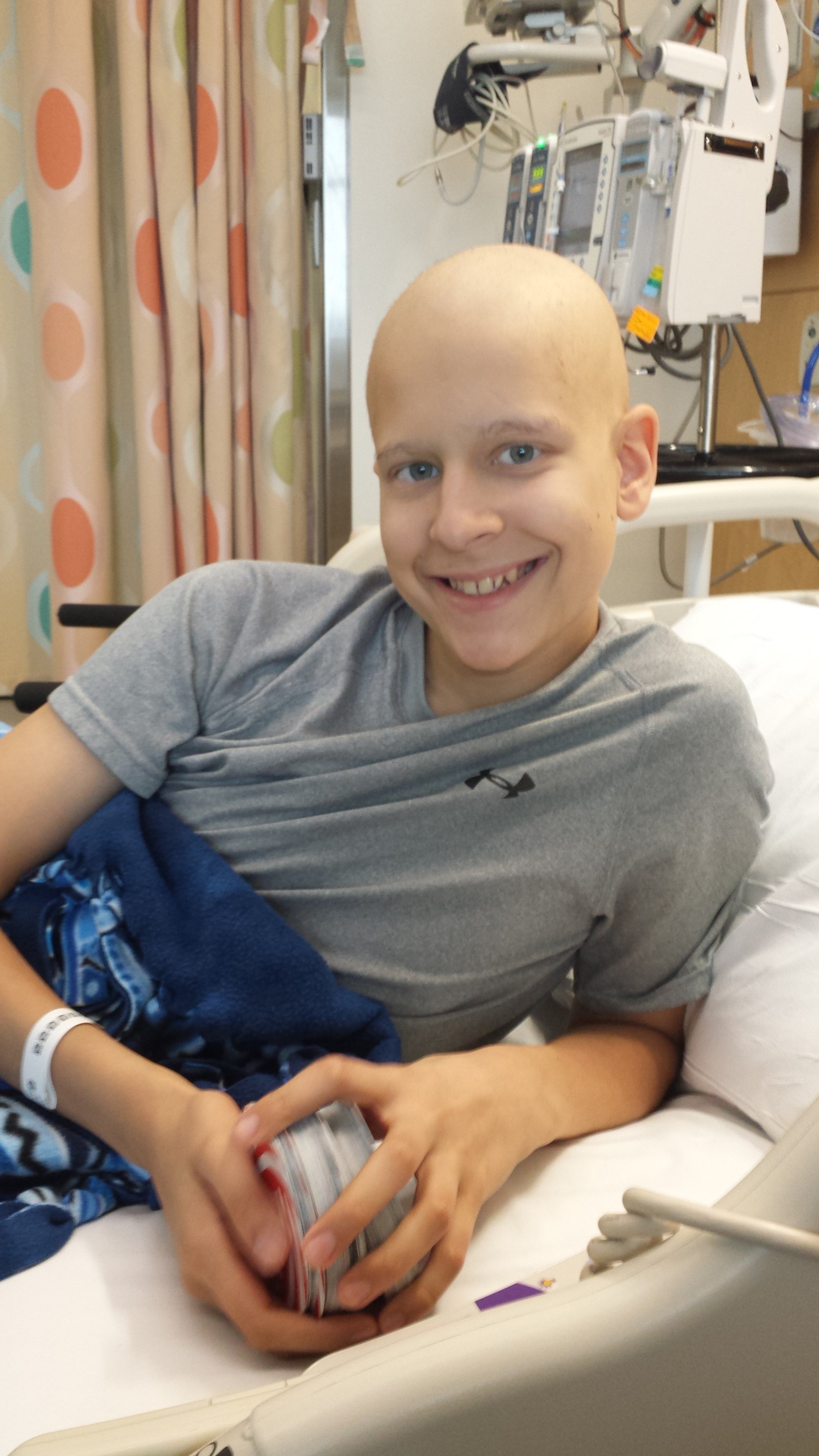

Guest blogger Michael Albrecht is a three-time survivor of Ewing’s Sarcoma, a cancer that forms in bone or soft tissue. He was first diagnosed at age fourteen, on the last day of eighth grade.

He was named a Children’s Cancer Cause College Scholar in 2020, and he currently serves on our Stewart Initiative Survivorship Advisory Council, where he provides invaluable insight and perspective to help guide our survivorship programs and activities.

Even though I am only 22 years old, I have had Ewing’s Sarcoma three separate times, first occurring on June 17, 2015. I was only 14 years old when I began chemotherapy and when I received a limb salvage surgery.

I showed no evidence of disease for three years, but then I was diagnosed with my first relapse on January 29, 2019. This time, I received chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant. These treatments held off the cancer for a year and a half, until my second relapse on February 9, 2021. I received chemotherapy and a left lower lobectomy in the months following this reoccurrence.

While I have showed “No Evidence of Disease” for over twelve months now, I continue to take an oral chemotherapy in hopes that it will prevent any further reoccurrences of Ewing’s Sarcoma.

This seven-year journey has allowed me to examine many facets of the institutions that practice and research medicine.

One thing has become clearer than anything else: much effort is being dedicated to cancer research. Luckily, it has not been in vain. Cancer research has contributed greatly to our understanding of how cancer functions and how to best treat it, resulting in decreased mortality rates and increased quality of life among cancer survivors.

However, an important component in one’s battle with cancer has been largely overlooked — the patient’s mental wellness. My own cancer has occurred or relapsed during the most stressful times of my life. While going through cancer treatment often eliminates the stressor that was bothering me before, it brings on many new stresses.

During the first battle with cancer, everything seemed to be mapped out. The type of chemotherapy was selected on my behalf, the surgery was scheduled, and off I went to my new life in the hospital. However, during my second and third battle with cancer, I was exposed to more medical choices than before. Obviously, much of this choice was due to my newfound “adult” label, but it has become apparent that there was more going on.

I am no longer getting the most effective treatment based on prior research, but I am becoming a part of research, with each decision I make essentially making me a new data point for future patients to reference. The choices that I make can provide researchers with information on how well certain treatments work.

As you might imagine, the uncertainty associated with trying something that has not been thoroughly proven to be effective can cloud the mind with anguish. When it comes to cancer treatment, choice allows me to factor in my own "quality of life” standards and take a treatment to suits my goals and desires.

But choice can also mean something far worse. When I have a choice to make with my health, it often means that not enough research has been conducted to show a clear advantage of picking one treatment over the other. This creates insurmountable amounts of stress, as one can never be quite sure if he or she is making a good decision. Furthermore, it is not always a concern over what to take, but rather how much to take, how often to take it, and for how long.

Currently, simple questions like “how often should I receive scans post surgery?” may result in different answers if you ask different people. Different answers may be attributed to the doctor’s preferences, the institution’s standard of care, the insurance company’s financial obligations, or worse: “whenever the patient chooses.” The simple question of “how long should I wait before receiving the next scan?” impacts a patient’s stress level, mental health at large, and (possibly) the chances of a cancer relapse.

Before being able to come up with a more concrete answer or formula, high-quality research is a necessity. Upon expressing my opinions with research teams around the world, I have become further confident in my assumption that the medical field does not currently have the scientific evidence needed for surgeons to know the optimal frequency and mode of surveilling patients after surgery.

I don’t wish for anybody to have to go through cancer treatment, especially at 14 years old. But the reality is that millions of Americans will go through some of the most difficult moments of their lives when they face a diagnosis. Their road is long and their way is hard, but by investing in research today, we will pave the way to easier and (God-willing) more successful treatments for so many adults and children.

Editor’s Note: Progress in pediatric cancer research is almost entirely dependent on federal funding. Join us in asking Congress to provide strong funding to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in fiscal year 2024 by sending a message here.